Sarah Womack is former political correspondent and social affairs correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, with a particular interest in women’s issues and social science.

Here she writes about International Women’s Day, and how ESRC research contributes to its 2017 campaign theme #BeBoldForChange

There’s a fascinating piece of social history that goes like this; in the beautiful coastal outpost that is Aldeburgh, Suffolk, three young women gather in 1860 to plot their careers. One said she would become Britain’s first female doctor. One would pursue the right of women to go to university.

The third, only 13 at the time, would press for women to have the vote.

Remarkably, all fulfilled their ambitions. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson became a doctor (the centenary of her death is commemorated this year). Emily Davies co-founded Girton College, Cambridge, Britain’s first residential college for women offering an education at degree level. Elizabeth’s sister Millicent Garrett (later Fawcett), helped achieve women’s suffrage; her society, The Fawcett Society, remains a potent campaign force on women’s issues.

So, on International Women’s Day, what would our three pioneers make of progress 157 years later – on women in education and science, the career-stalling effects on women having children, gender inequality generally?

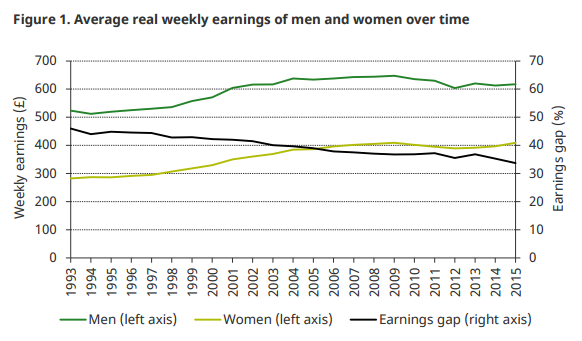

Gender has been the focus of key ESRC research which unearthed the good, the bad and the plain depressing. Our trio of trailblazers would see an “incomplete revolution”, says a major investigation into gender equality which expressed “deep concern” about prospects for closing the gender pay gap. Many UK companies saw “little incentive” for ensuring the work-life balance of men and women was equitable, they said. Legislation was needed to force the hand of business.

Fortunately, it is coming. Under new laws next month (April 2017), large firms will have to calculate their gender pay gap, and publish details by April 2018.

Meanwhile Emily Davies would surely be impressed that UK women are now 35 per cent more likely than men to go to university, with the gap widening every year. A girl born in 2016 will be 75 per cent more likely to go to university than a boy, if current trends continue.

But as Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, told The Times, the wage gap between university-educated men and women has barely shifted in two decades. Only among the least well educated has there been a clear catch-up.

“It’s worth dwelling on that,” he says. “In the past 20 years there has been no progress at all in closing the wage gap between highly educated women and similarly well-educated men.”

Yes, but women go off and have children is the common riposte.

Well, for those without children working at least 20 hours per week, the wage gap is still 10 per cent on average, and six per cent for those aged under 35, says IFS research funded by the ESRC and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. And of course, men have children too. But for women with children over about 11, the wage gap with men is, “staggeringly, more than 30 per cent”.

There are concerns the gender pay legislation will not go far enough; there is no requirement for employers to distinguish pay gaps by age group or to identify differences in pay between employees with children and without.

But it is a welcome move. I have a 12-year-old at a London girls’ school who recalled a comment her classmate made: “So men earn more than women. Get over it. It’s just life.” Even now it seems, pre-teen girls are acclimatised to pay inequality, even normalising it.

Where equality is happening successfully is on the domestic front. It sounds less important, but for women it is crucial as they assimilate the competing claims of home and work.

The study, which spanned Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Britain, found men are actually happier when they make an equal contribution to chores like cooking, washing and cleaning. Academics concluded that “more men support gender equality, so feel uncomfortable if the woman does most of the housework, and women are making their dissatisfaction with lazy partners plain”.

But gender inequality does persist in the workplace, and the ESRC is funding projects to see whether political change, such as devolution, is beneficial for women.

The answer is yes, says Professor Paul Chaney of Cardiff University’s School of Social Sciences.

“Wales scored a world-first when the National Assembly for Wales achieved 50:50 male-female representation following the 2003 Welsh elections,” he says. Currently, women constitute 42 per cent of Assembly Members – compared to 34.9 per cent women MSPs elected to the fifth Scottish Parliament, and 30 per cent of MLAs elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly following the March 2017 election.

“Gender equality is more firmly embedded in public policy than before. There are specific Welsh laws to underpin this, and political decision-making structures are more open to women,” he added.

In some areas, progress has been disappointing: “If you look at the largest civil society organisations in Wales, just over a third of chief executives are women,” Professor Chaney acknowledges.

“But devolution is very much a force for good. The Brexit vote is, however, deeply troubling for gender equality in Wales – and the UK. It was European considerations that led to our first major equality laws in the 1970s, and Objective One Economic Aid for Wales in the early 2000s forced the Welsh Government’s Executive Agency to take equality matters seriously.”

In the UK and further afield, the ESRC is also examining gender inequality in science.

As Nicole Gross-Camp, lecturer at the School of International Development, University of East Anglia, points out: “Women are earning approximately half of the doctoral degrees awarded in science and engineering. But there remains a despairing and pernicious gap at the post-doctoral level, and beyond. Women comprise only 21 per cent of full professors in science and five per cent in engineering, earning 16 per cent less than their male counterparts in the US.”

Research suggests these inequities persist in part due to greater childcare expectations falling on women, as well as the lack of females in senior positions, Nicole says.

“When we look at the statistics, and listen to the stories of girls and women that have left science, they are notably higher and different than those of men. Societal obstacles are a big barrier and one that is shifting but s-l-o-w-l-y, particularly at higher levels. That said, we still have a way to go to even out the handicap (and blessing) of birthing children.”

What difference does it make when there is a lack of women in science? It stymies those women who want to pursue it, of course, and denies the field of their talents. It may also mean women not getting the quality of healthcare men receive, according to an article in National Geographic by Marguerite Del Giudice.

She says women with heart disease have been misdiagnosed in emergency rooms because “for decades what we know now wasn’t known: that they can exhibit different symptoms from men for cardiovascular disease. Women also have suffered disproportionately more side effects from various medications because recommended doses were based on clinical trials focused on men”.

On the broader issue of gender equality in science, there are some grounds for optimism, says Nicole; 500 Women Scientists, a movement in its infancy, counters anti-women (and anti-science) sentiments and already boasts more than 16,400 signatories from 109 countries.

“500 Women Scientists is an example of the ways in which women (and the world) are organising against perceived injustices – in this case directly against women in sciences but arguably about women that are learned more broadly.”

She urged more “critical and productive actions” that recognise women as individuals with aspirations and potential on a par with their male counterparts.

“Those actions pertain to the need to challenge gender stereotypes and in particular equalise the burden of childcare that often falls on women (in heterosexual relationships). This is a complex task and requires consideration at multiple levels (and countries). I find gender stereotyping alive and well in the UK (and US) and very much ‘in bed’ with the gender gap in ‘male’ professions – science, engineering, technology and maths.”

Emily, Elizabeth and Millicent would surely be amazed at their legacy, but not complacent. Millicent’s society is already using the EU Referendum as a call to action on women and equality.

We owe them.